Sport

Taylor Fritz and Frances Tiafoe’s intertwined journey to the U.S. Open semifinals

About a dozen years ago, a couple of 14-year-old boys arrived in Boca Raton, Fla. They were there for a United States Tennis Association camp, as promising junior players.

One was a Black kid from suburban Washington, D.C. The son of refugees from Sierra Leone, he was a natural athlete with magic hands and the biggest grin around. His mouth never stopped. His father was the maintenance guy at the local tennis center back home, and there were many nights during his childhood when the kid and his brother slept in a spare room there, because their mother was working late and their father had projects to take care of at work.

The other was a White kid from southern California, the heir to a retail fortune. He grew up in family homes with art collections. Both his parents were former professional tennis players, though it wasn’t yet clear whether he was headed down that path. He had big feet, that stumbled over each other when he stopped and started, a lanky physique and hands that sent balls careening into the back fence as often as they landed inside the lines.

This is where the friendship between Frances Tiafoe and Taylor Fritz began; where their tennis lives first intersected; and where they took their first steps towards Friday, when they will contest a semifinal duel at the U.S. Open, on Arthur Ashe Stadium.

Bring up either one’s name with the other, and they both break into some combination of smiles, shakes of the head and eye-rolls. They convey a kind of amazement at how the other one rolls through life.

“An odd cat,” is how Tiafoe playfully described Fritz, especially during those early teenage years.

“Frances is just Frances,” Fritz will often say.

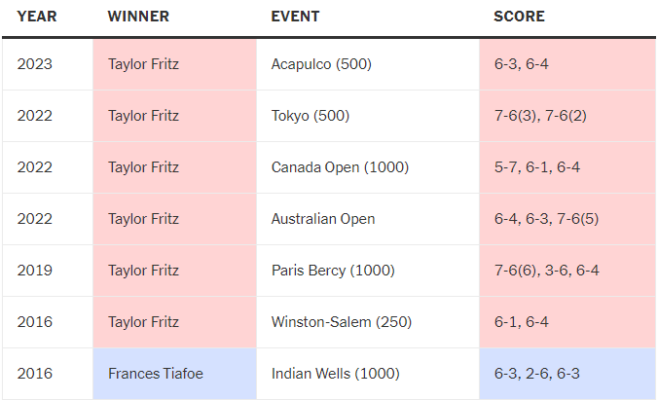

Tiafoe is the natural, who has long struggled to find his motivation. Fritz is the unnatural, who has outworked his best friends and compatriots to set the standard for American men in recent years. Coaches at that Boca Raton camp 12 years ago would never have believed in that possibility.

Tiafoe passes the night after a good match on the NBA sidelines, never happier than when he is rubbing shoulders with the stars of the hardwood and Hollywood that sit courtside and in suites for his matches. Give Fritz a video game and a lock on his hotel room door and he’s good to go for the night.

On the road, Fritz gets the reservations at the happening restaurants, with an assist from his girlfriend, social media influencer Morgan Riddle. Tiafoe is prone to forgetting to show up to dinner reservations.

Their dichotomy extends to the tennis court. Tiafoe is the showman, working the crowd, riding his emotions and theirs into battle as he scurries across the court, working his way forward to try to finish points at the net.

Fritz’s emotions can be his biggest enemy. Working a crowd? A distraction from the annual, all-encompassing grind to push his ranking higher and maintain his spot as the American No. 1. Tiafoe freely admits that he only gets truly engaged in the summer, peaking a little bit for Wimbledon, but really saving his energy for the American hard-court swing. That’s when he begins to buzz. After beating Grigor Dimitrov, when asked if he would like to take his U.S. Open form and feelings into the whole tennis season, he grinned.

“Probably bottle it for August.”

It goes back to all those national camps and training groups, in Florida or at Jose Higueras’s ranch in Palm Springs. Tiafoe and Tommy Paul, the third member of their teenage quad (with Reilly Opelka, who has been injured the past two years) were so much better than Fritz back then that they used to have contests to see who could beat him faster.

Fritz wouldn’t know about this until later. By then he was getting his revenge, surging ahead of them in his late teens and becoming the first of the group to enjoy success as a professional. Sitting around the dorm rooms, passing the time as teenage boys do, Fritz often ended up as the butt of friendly ribbing.

“Big goofy guy like that, you know he’s going to be catching it,” Tiafoe said.

But Fritz has been getting the last laugh for a while now though.

“Taylor was always motivated to work harder,” Higueras said Thursday from his home in Idaho.

A clay-court specialist who helped in the development of the generation of American men that included Pete Sampras, Higueras became the co-director of player development for the USTA in 2008. In March 2024, Higueras excoriated the organization for “wasting millions” in funding, having left his full-time role in 2017.

He told the organization that rebooting a pipeline that had run dry was a decade-long project. Fritz and Tiafoe entered his orbit in his first years on the job. Back then, anyone would have bet on Paul or Tiafoe to be the breakout stars, except maybe Higueras, who would have advised hanging on to your money.

“You just never know how players are going to turn out,” Higueras said.

He thought this day would come as long as three years ago, but Novak Djokovic, Rafael Nadal and Roger Federer took longer to fade than anyone might have guessed. Tiafoe had his motivational lulls, and the sport kept shifting on Fritz. Just when he began to master moving side-to-side, his weakness in terms of finishing points at the net became a serious problem.

It’s also possible that they are right on time. They are 26 now. Tennis is known for its prodigies, generational stars like Carlos Alcaraz, who won his first Grand Slam when he was 19. But most men reach their athletic prime between 25-30.

From a U.S. tennis perspective, it’s about time.

Americans meeting in the final stages at the Billie Jean King National Tennis Center in Queens used to be as regular as the slight chill in the air that arrives for early September evenings in New York. No longer. While the women have soared, two American men haven’t played each other in the semifinals since Andre Agassi beat Robby Ginepri in 2005.

“It’s going to be just electric,” Fritz said of the opportunity.

Tiafoe has struggled against Fritz as a professional. But as he said the other night, “It’s different on Ashe,” where Tiafoe usually has 24,000 people turning the stadium into a house party, with him holding the aux cord.

He’ll have to share it this time. May the best friend win.