Uncategorized

Ethiopian Airlines Crash Kills at Least 150; 2nd Brand-New Boeing to Go Down in Months

Ethiopian Airlines Crash Kills at Least 150; 2nd Brand-New Boeing to Go Down in Months

At least 150 people were killed when Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 crashed early Sunday. It was the second such disaster involving a brand-new Boeing 737 Max 8 in months.

ADDIS ABABA, Ethiopia — A jetliner with passengers from at least 35 countries crashed Sunday shortly after leaving Ethiopia’s capital, killing all 157 people on board and renewing concerns about the new model of aircraft involved in the accident, the popular Boeing 737 Max 8.

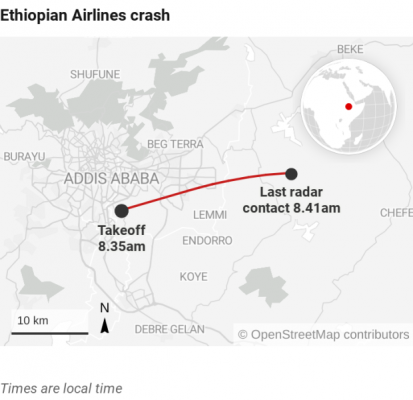

After taking off from Addis Ababa in good weather and with clear visibility, Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302, bound for Nairobi, Kenya, struggled to ascend at a stable speed, according to flight data published by FlightRadar24. The pilot sent out a distress call and was cleared to return to the airport, Bole International, the airline’s chief executive told reporters.

But the plane — the same Boeing model that went down in Indonesia in October, killing all 189 people on board — lost contact with air traffic controllers six minutes after takeoff. It then plummeted to the ground near Bishoftu, a town southeast of the capital.

“At this stage, we cannot rule out anything,” said Tewolde GebreMariam, the chief executive of Ethiopian Airlines, which has a solid reputation for safety among aviation experts and is in the midst of a major expansion as part of its effort to make air travel easier across Africa.

Images from the vast, smoky crater at the crash site revealed a grim tableau. Workers loaded black body bags into a truck, while plane fragments and various items from the flight — cigarettes, shoes, napkins with the Ethiopian Airlines logo — were strewn across the field.

Flight 302 — a two-hour shuttle between two of the busiest capitals in East Africa — was carrying passengers from at least four continents. The dead included 32 Kenyans, 18 Canadians, nine Ethiopians, eight each from the United States, China and Italy, and seven from Britain, the airline said. The French Foreign Ministry said nine of its citizens were aboard.

The passengers also reportedly included delegates traveling to Nairobi for a weeklong United Nations Environment Assembly that was scheduled to start on Monday.

While the cause of the crash was unclear, the disaster is certain to raise more doubts about the safety of the 737 Max 8, one of Boeing’s fastest-selling airplanes.

The plane, delivered to Ethiopian Airlines in November, was new, just like the Lion Air airplane that plunged nose down into the Java Sea last October, minutes after taking off from Jakarta, the Indonesian capital.

Flight 302 took off in good weather, but its vertical speed became unstable right after takeoff, fluctuating wildly, according to data published by FlightRadar24 on Twitter. In the first three minutes of flight, the vertical speed varied from zero feet per minute per hour to 1,472 to minus 1,920 — unusual during ascent.

“During takeoff, one would expect sustained positive vertical speed indications,” Ian Petchenik, a spokesman for FlightRadar24, said in an email on Sunday.

Crashes involving new planes in good weather are rare.

The Lion Air accident also involved a plane that crashed minutes after takeoff and after the crew requested permission to return to the airport. The Lion Air pilots struggled to keep the plane ascending, with the jet’s nose forced dangerously downward over two dozen times during the 11-minute flight.

The National Transportation Safety Board in the United States said it would send a four-person team to assist Ethiopian authorities investigating Sunday’s crash. The Federal Aviation Administration said in a statement, “We are in contact with the State Department and plan to join the N.T.S.B. in its assistance with Ethiopian civil aviation authorities to investigate the crash.”

Boeing said in a statement on Twitter that a technical team was ready to provide assistance at the request of the safety board.

In the Lion Air crash, officials are investigating whether changes to the Max 8’s automatic controls might have sent that flight into an unrecoverable nose dive.

An investigation by Indonesian authorities determined that the Lion Air plane’s abrupt nose‐dive may have been caused by updated Boeing software that is meant to prevent a stall but that can send the plane into a fatal descent if the altitude and angle information being fed into the computer system is incorrect.

The change in the flight control system, which can override manual actions taken in the Max model, was not explained to pilots, according to some pilots’ unions.

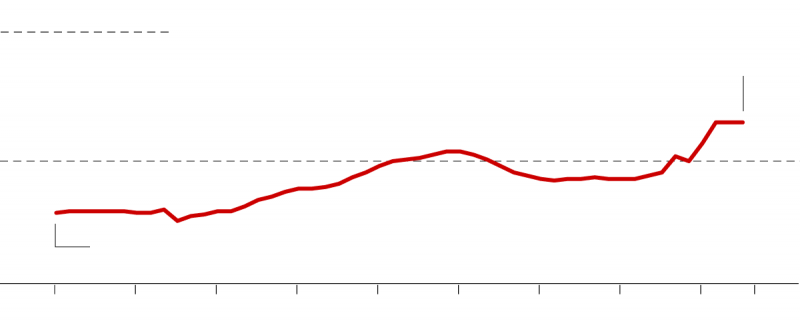

The Climb of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302

Data from Ethiopian Airlines flight 302 shows its altitude fluctuating up and down shortly after takeoff, at 8:38 a.m., until radar contact was lost, at 8:41 a.m. The plane crashed a few minutes later. The altitude shown is compared to mean sea level, not ground level.

Global alerts were sent to notify pilots flying the Max about how to counter the anti‐stall system.

Families of some of the victims of the Lion Air crash are suing Boeing, arguing that the company failed to properly inform pilots of the updated software.

Lynette Dray, an aviation expert and senior research associate at University College London, said that the Max model has a more efficient engine than the previous 737 aircraft, but that “it’s not revolutionary new.”

Boeing has delivered more than 350 Max 8 models to airlines around the world, including in the United States, Canada and Europe. The planes entered service in 2017, generally replacing older 737’s.

While both of the Max 8 planes that crashed experienced similar dips and climbs during their ascents, the airlines flying them have notably different reputations. Even before the October crash, Lion Air had a notorious safety record.

Ethiopian Airlines, Africa’s biggest carrier, is widely considered its best and has expanded rapidly in recent years, opening new routes all over the continent.

The airline has ordered 30 of the Max 8 planes and already had five in its fleet, with the first being delivered last year, according to FlightRadar24.

Boeing had promoted the model by minimizing the costs of upgrading, saying the 737 Max 8 required little additional training for pilots who had flown a previous version of the plane. That is believed to have been a key in winning orders from airlines that had also been considering an updated model, the Airbus A320, from Boeing’s archrival.

There has not been a crash involving Ethiopian Airlines since January 2010, when a Boeing 737 crashed into the Mediterranean Sea shortly after it took off from Beirut, Lebanon. None of the 90 people onboard that flight — 82 passengers and eight crew members — survived.

Ethiopian Airlines said on Sunday that the captain of the flight, Yared Getachew, 29, had more than 8,000 flying hours and a “commendable performance.”

The plane, which underwent a “rigorous first check maintenance” on Feb. 4, had flown back to the Ethiopian capital from Johannesburg, South Africa, on Sunday morning, according to the airline.

“Ethiopian Airlines is very, very highly regarded; it’s part of the Star Alliance,” Graham Braithwaite, a professor of safety and accident investigation at Cranfield University in Britain, said by phone on Sunday.

Professor Braithwaite was referring to the airline alliance that includes carriers like Lufthansa, Singapore Airlines and United.

The lead investigation will start in the country where the crash happened, Ethiopia, he said, but other countries will also be involved — Kenya and the United States, independently of Boeing, because the aircraft was made in the United States.

“They’ll want to work quite swiftly,” Professor Braithwaite said. “It’s in nobody’s interest that a failure goes unknown.”

The priority will be to make sure there is no link between the crashes in Ethiopia and Indonesia, and other countries and airlines will no doubt be watching closely, given the plane’s global popularity.

At Nairobi’s Jomo Kenyatta International Airport, distraught family members and friends gathered at an emergency center established by the authorities. Another emergency center was set up at a nearby hotel within the airport to provide counseling.

“I came to the airport to receive my brother but I have been told there is a problem,” one family member, Agnes Muilu, told The Associated Press. “I just pray that he is safe, or he was not on it.”

Flight 302 was popular with aid workers based in Ethiopia who needed to exit and re-enter the country regularly so as not to violate work permits.

The executive director of the World Food Program, a United Nations organization, said on Twitter that staff members from the group were among the dead. Aid workers from the United Nations, Catholic Relief Services and other organizations were also aboard the plane.

Ethiopia, with about 100 million people, is the second‐most populous nation in Africa. Since elections in March, the new prime minister has been embarking on a series of political reforms, chiefly to officially end two decades of hostilities with Eritrea, a neighboring country and longtime rival.

The country’s flagship carrier has undergone a major expansion, more than doubling its staff to 11,000 employees in the past decade, with the goal of easing air travel in a part of the world where flying is notoriously complicated.

It added nonstop flights, for instance, from Newark to Lomé, Togo, a hub for the airline, that then continue on to Addis Ababa.

In Africa, Ethiopian has a reputation for having a newer fleet than other airlines, for operating flights that are mostly on time and for having accommodating schedules.

Professor Braithwaite described Ethiopian Airways as “one of the best operators in Africa.”

Updated as of 5pm 3/10/19: 1/2 The U.S. Government, the Embassy team, & the American people extend our sincere sympathies to all those who lost loved ones in the crash this morning of Ethiopian Airlines flight 302. https://t.co/VZxEHYFPUK

— U.S. Embassy Addis (@USEmbassyAddis) March 10, 2019

Hadra Ahmed reported from Addis Ababa; Norimitsu Onishi from Johannesburg, South Africa, Dionne Searcey from Dakar, Senegal; and Hannah Beech from Bangkok. Reporting was contributed by Jennifer Jett from Hong Kong; Iliana Magra from London; Reuben Kyama from Nairobi, Kenya; Elsie Chen from Beijing; Thomas Kaplan from Washington; Chris Buckley from Beijing; Dan Bilefsky from Montreal; and Ivan Nechepurenko from Moscow.