News trend

Despite weeks of threats, ICE raids begin with a whimper yet still stoke fears

Long-threatened Immigration and Customs Enforcement raids appeared to begin Sunday on a decidedly small scale, with a scattering of arrests that nonetheless sparked new fears in immigrant communities.

The raids — hyped for weeks by President Trump — were to take place in major U.S. cities including Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, Chicago, Miami, Denver, Atlanta, Baltimore and Houston.

As of Sunday evening, there were no reports of arrests in the Los Angeles area. And the widespread raids that some feared failed to materialize.

In Florida, ICE agents were seen knocking on doors near Miami International Airport on Sunday and in the migrant farming community of Immokalee on Friday, but there had been no reports of arrests, said Melissa Taveras of the Miami-based Florida Immigrant Coalition.

“We don’t know if they’re doing it on purpose — saying these cities are the targets so then smaller places are targeted,” Taveras said.

Taveras said migrant advocates were advising families to memorize the phone number of a relative or an attorney they could call if they were detained by ICE, and to ensure a relative knew their full name, date of birth and what location they’re being taken to so that they could try to get released.

She said she has been in contact with migrant families hiding in their homes. She said it felt as though they were preparing for a storm.

“The overall environment is very much like a hurricane: When is it going to come, is it going to hit us, is it going to move north?” she said.

In Houston, there was no sign of ICE raids early Sunday.

“It’s actually really quiet. We’re driving around and it’s really empty,” said Cesar Espinosa, executive director of immigrant advocacy group Fiel Houston.

Espinosa was driving to check out a report that two migrants had been picked up by ICE at an apartment complex late Saturday. Nearly a dozen churches have volunteered to house migrants during the raids, providing food and other supplies. But many were sheltering in place.

“We’re advising people to just continue with their lives,” Espinosa said, “and know their rights so they know what to do.”

By late Sunday afternoon, Venus Rodriguez was reaching out to migrant families hiding at home and preparing to emerge Monday.

“They’re going to attempt to go to work, because they need the money,” said Rodriguez, 43, a U.S. citizen and a community organizer on Houston’s north side. “It’s a scary situation for a lot of them.”

While some officials have said that only recent migrants with deportation orders will be targeted in the ICE raids, she said, “a lot of them are not trusting that. They think they might just start picking people up.”

Rodriguez attended Mass at a local Catholic church Sunday where the pews were emptier than usual.

“That’s one place you should feel safe,” she said. “This is horrible.”

On Saturday, New York Mayor Bill de Blasio said his office was “receiving reports of attempted but reportedly unsuccessful ICE enforcement actions in Sunset Park and Harlem.”

Three attempted ICE raids were reported later — two in the Sunset Park area of Brooklyn and one in Harlem — according to the New York Mayor’s Office of Immigration Affairs.

“No arrests were made to our knowledge,” the office said in a statement.

Jojo Annobil, executive director of New York-based Immigrant Justice Corps, said that even though no arrests had been made in the raids, “people are still scared.”

“It’s going to carry over into the week, with children scared their parents won’t come home” from work, he said of the ICE raids. “It scares neighborhoods. People are on edge, because nobody knows who they are targeting.”

Annobil said his group, which includes 54 lawyers in New York, New Jersey and Southern states, was prepared to respond by representing migrants with deportation orders and filing motions to reopen their cases.

Sunday’s ICE operation was targeted at a couple of thousand people with court removal orders, but it also was to include “collateral” deportations in which agents detain immigrants in the country illegally who are not intended targets but happen to be in the area.

A main focus of the raids is families, many of whom failed to show up for a court hearing on their case. Also targeted are children who arrived at the border without an adult and were released to a parent or other sponsor but ordered deported, said Greg Chen, director of government relations at the Washington-based American Immigration Lawyers Assn.

An ICE spokesman wouldn’t give many details, and it remains unclear how many people will be swept up. Trump has tweeted about the raid for nearly a month, and that has immigrants here illegally on edge.

On most Sundays, Los Angeles resident Elias, who didn’t want his last name used out of fear, said he would take his girlfriend and toddler to the beach or the park.

Not this Sunday.

Instead, the three hunkered down in his MacArthur Park apartment. His brother — who doesn’t have legal status and lives with them for the moment — called in sick to work.

Elias planned to order meals online for delivery. He was careful to answer the door only to people he knew.

Elias doesn’t have a removal order. The Guatemalan immigrant, who arrived in the U.S. when he was 15, said he had a special visa allowing him to temporarily live and work in the country legally.

Still, he said he was petrified of setting foot outside his home. He’s not alone. He said many of his friends had bought a week’s worth of groceries on Saturday in preparation for the anticipated raids.

Elias used vacation days to take an entire week off from his work at a cafe.

“I feel like there is no way to hide,” he said, “but just pray to my God to protect me.”

The MacArthur Park area, which for decades has served as a port of entry for new arrivals from Mexico and Central America, is among the most crowded and densely developed sections of Los Angeles. It is a place where immigrant families gather to socialize and browse myriad shops and street vendors offer items and services as varied as fresh mangoes and cheap furniture, used clothes and check-cashing services.

The prevailing mood among owners of businesses along the usually bustling streets surrounding the park was one of unease and anger on Sunday as the threats of raids kept away more than two-thirds of their patrons.

Many loyal customers were afraid even to show their faces for fear of being questioned or detained, and the nearly empty 30-acre park — usually a magnet for throngs of people on a summer weekend under azure skies — worsened the economic impact for a community that was already feeling on edge.

Leaning against the counter of a Total Wireless store, salesman Biviano Oxlaj, who earns commissions on sales, shook his head in dismay and said, “I’ve been staring at the front door all day, just hoping a customer shows up.

“Business is down by 75%, and it’s been that way since Saturday,” he said. “But since this is all because of an order from the White House, there’s not much anyone can do but wait for it to pass like a storm cloud.”

A block away, Juan Castenada, a clerk at Bargain Dica, where many items cost a dollar, looked out on empty aisles. “People are afraid to come outside,” he said. “So, it’s going to be a long, slow day.”

A few doors down at Shalom Furniture, salesman Herman Ventura would not argue with any of that: “The few people out on the street today are nervous and looking over their shoulder. The rest just stayed home.”

Edgar Barrera noticed that his Koreatown neighborhood was quieter than usual Sunday. He didn’t see many families walking the streets, there were fewer people attending morning church service, and the nearby Guatemalan and Salvadoran bakeries were practically empty.

“It has been totally silent around here since yesterday,” Barrera, 59, an immigrant here illegally from Guatemala. “People are terrified to go out on the streets.”

Barrera manages a store that helps clients send packages to Guatemala at a cheap price. He said he works seven days a week and plans to continue doing so.

“I can’t give myself the luxury of not going to work,” he said. “I have to pay rent, I have to pay for food…. My mother is sick and needs medicine, and I’m the only person who can pay her medical bills.”

He says that word of the ICE raids spread quickly through the Guatemalan community, primarily through Facebook. Many people stayed home Sunday or found different ways to stay out of sight, he said.

Barrera is avoiding driving on main avenues today, and took the side roads to get to work. But he’s not changing his routine too much.

“I’m tired of running away all the time,” he said. “I’m hoping that if I stay calm, nothing will happen.”

Barrera said he can’t afford a lawyer to help him gain legal status — so if he is apprehended, he’s going to have to accept going back to Guatemala after a life built up for more than 20 years in the United States. It’s clear that his community is scared of ICE raids, or la migra, as he calls immigration officers, but there’s not much he thinks he can do about it.

“The fear is already instilled in all of us,” he said. “But I’m going to keep working the same as usual.”

On 4th Street in Santa Ana, some street vendors reported dismal sales.

Sylvia, a street vendor who only gave her first name because she’s in the country without legal status, said sales were down by at least half. By noon, she usually has at least 30 customers. At 2 p.m. Sunday, she’d had only 15.

“It’s slow because many people are staying home,” she said. “They just aren’t coming because of what they’re saying in the news… because of the raids.”

Sylvia, who has lived in the U.S. for 15 years, did her best to keep busy. She patted down glass soda bottles into a large tub of ice.

She said most of the street vendors were afraid to show up for work but did so anyway.

“I don’t have papers, but I leave my fate in the hands of God,” she said. “If God says I have to return to Mexico, I’ll return.”

She pulled on her apron and recited her sales pitch to the few passersby. “Come on over,” she chanted in Spanish. “We have fruit, mangoñeadas, tostilocos, chicharrones, water, sodas and snow cones.”

As the threat of raids looms, controversy continues to swirl around conditions in some of the country’s migrant detention centers.

On Friday, reporters accompanying Vice President Mike Pence on a tour of the McAllen, Texas, Border Patrol station’s migrant detention center said about 400 men were crowded into hot, fenced pens with a horrendous stench. The men appeared dirty and said they had been held for more than a month, had not showered in over a week and wanted to brush their teeth.

Border Patrol officials confirmed that some men had not showered in 10 to 20 days but insisted the facility was air conditioned and that the men were able to brush their teeth.

On Sunday, Trump tweeted his own account of what the tour revealed and derided an earlier report by the New York Times about the overcrowding and dirty conditions that hundreds of children and other detainees had had to endure.

“Friday’s tour showed vividly, to politicians and the media, how well run and clean the children’s detention centers are. Great reviews! Failing @nytimes story was FAKE! The adult single men areas were clean but crowded – also loaded up with a big percentage of criminals……Sorry, can’t let them into our Country. If too crowded, tell them not to come to USA, and tell the Dems to fix the Loopholes – Problem Solved!

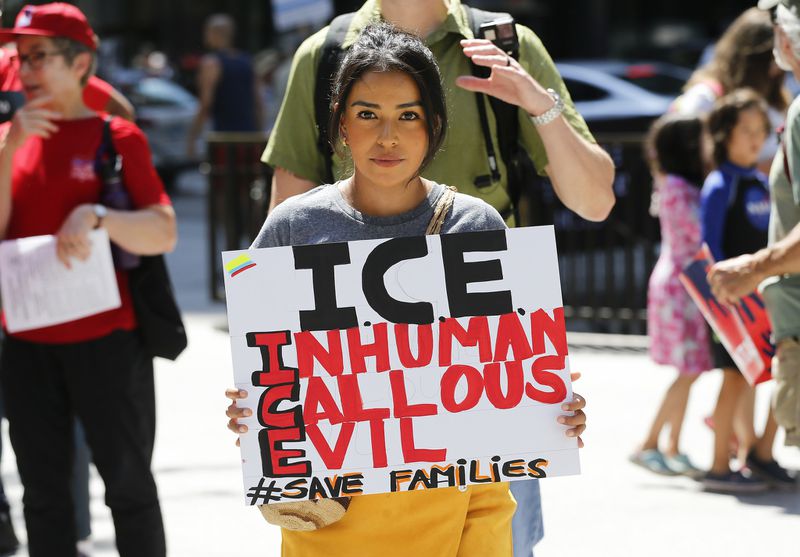

On the same day of Pence’s detention center tour, thousands of demonstrators staged protests across the country, including Los Angeles, to denounce the ICE raids and the Trump administration’s hard-line immigration policies. Appearing on CNN on Friday night, L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti chastised the ICE operation as chaotic and inhumane.

“These are people going to church wondering if there’s going to be [ICE agents there] when they come out of services,” Garcetti said. “It will spread fear to that entire community and to the U.S. citizens that are a part of their families.”

In addition to Garcetti, Los Angeles Police Chief Michel Moore, L.A. County Sheriff Alex Villanueva and other leaders have denounced the tactic.

Across the country, as in L.A., immigrants reportedly were skipping work and hiding out; a team of immigration lawyers was descending on a detention facility in Texas; activists were staffing tip hotlines that were ringing off the hook in Tennessee; and a group of advocates had launched a preemptive lawsuit in New York.

In San Francisco, the American Civil Liberties Union filed a preemptive lawsuit Thursday in U.S. district court seeking a temporary restraining order that would force ICE to allow detainees access to legal services. Lawyers said immigration processing centers, where detainees could receive legal advice, were closed on Sundays and that local immigration officials as a matter of routine refused requests for access to detainees on Sundays.

They worry that detainees could sign agreements to be removed from the country before receiving legal advice. Unlike in criminal court, immigrants do not have the right to government-appointed lawyers.

“ICE claims they’re giving people a list of phone numbers of pro bono agencies, but if they call, those numbers are useless — they can call that agency [on a Sunday] but no one is going to answer,” said attorney Hamid Yazdan Panah, an advocacy director of the California Collaborative for Immigrant Justice. “That moment when people are brought in and processed is when that imbalance of power is at its peak.”

Though Sunday’s raids were expected to specifically target families who had been ordered deported, ICE continues to conduct routine targeted enforcement operations throughout the country. In Los Angeles last week, dozens of migrants with criminal convictions were arrested by immigration authorities, and over the last few months roughly 900 such arrests have taken place nationwide, officials said.

These operations specifically target people who are a threat to public safety, such as convicted criminals and individuals who have violated immigration laws. By contrast, many of the families targeted under Trump’s enforcement initiative are people who have been issued final removal orders because they failed to show up for a court hearing on their case.

“For us it’s like, the government went through all this trouble to give you an opportunity … and then you didn’t even show up for court,” said an immigration official, speaking on condition of anonymity. “There’s a consequence — you violated the law and you didn’t go to court. That’s our job. That’s why it’s called law enforcement.”